Horror doesn’t always come crashing through a window. Sometimes, it waits. It hums through the still air, vibrating faintly in the creak of a rocking chair or the silence surrounding a crib. The most unsettling moments in horror films often arrive before the scream—when the room itself feels wrong, when the furniture seems to watch, wait, or remember.

From worn velvet settees in crumbling mansions to cold Scandinavian chairs in minimalist homes, horror films have long used furniture as more than just decoration. It’s a subtle form of storytelling. Chairs, beds, wardrobes—these objects sit still, but speak loudly. They tell us about the people who once used them, about the things that happened in their vicinity, and sometimes about the things that never left.

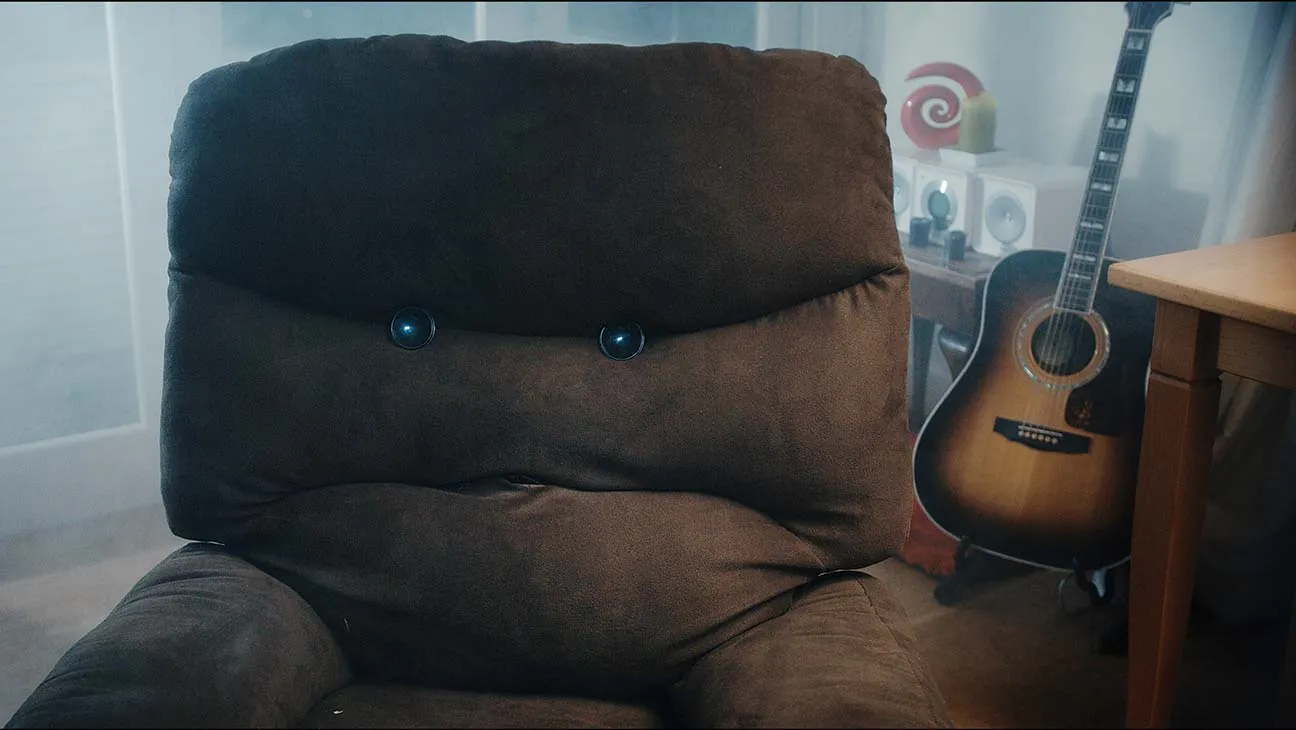

This article explores how horror films have used furniture across decades to deepen fear and tension. It’s not about the monsters in the room—but about what the furniture knows, what it hints at, and what it hides. From the stacked chairs of Poltergeist to the emotional weight embedded in Hereditary’s armchair, we’ll examine how furniture becomes a character in its own right, pushing horror beyond blood and into the psychological architecture of a scene.

Possession, Haunting, and the Furniture That Moves

In haunted houses and cursed nurseries, furniture doesn’t always follow the laws of physics. It glides, rearranges, rocks on its own. This movement—or the threat of it—is more than visual trickery. It’s a direct violation of the home’s unspoken contract: your furniture is supposed to stay put.

The Conjuring (2013) makes brilliant use of this. The Perron family’s antique rocking chair becomes a focal point—not because it’s grand or ornate, but because it moves subtly, as if reacting to something we can’t see. When it rocks by itself in a quiet room, it’s not just a jump scare. It’s a message. The house has a memory, and it’s leaking into the present.

In Poltergeist (1982), the stacking of kitchen chairs into a perfect, unnatural pyramid is an early signal that logic is no longer welcome in the house. It’s disturbing precisely because it’s so tidy. These aren’t chairs flung in rage—they’re arranged with surgical precision. The disruption is domestic and deliberate.

Then there’s Hereditary (2018), where Ellen’s armchair takes on symbolic weight after her death. The chair is positioned near the attic, where secrets lie. It doesn’t move, but it holds space. When Annie sees her mother’s ghost sitting in it, even briefly, the moment speaks volumes. The chair becomes a vessel of grief, history, and spiritual presence.

These instances show how horror toys with autonomy. Furniture becomes an intruder when it moves on its own—or worse, when it doesn’t move but seems to think.

There’s a psychological twist to this as well. The idea that something familiar—like a child’s crib or a living room couch—can act against you is more deeply unsettling than an external threat. It suggests your environment has turned on you. That the safe zones, the ordinary things, are no longer trustworthy.

This theme appears in lesser-known films as well. In The Babadook (2014), the mother’s chair becomes a resting place turned battleground as her sanity crumbles. It’s not haunted in the traditional sense—but it’s soaked with fatigue, anxiety, and isolation.

Possessed or haunted furniture disorients not because it attacks, but because it betrays the viewer’s expectations of domestic logic. Horror lives in the uncanny—the nearly normal. A chair that rocks without cause is frightening not because it moves, but because we know it shouldn’t. And still, it does.

Layout, Furniture Placement, and Claustrophobia

The shape of a room, the arrangement of its furniture—these are architectural choices, but in horror, they’re also psychological ones. Tight quarters and oddly arranged furniture make the viewer feel boxed in, watched, or exposed. Space becomes a weapon, and furniture is the architect’s favorite tool.

In Rosemary’s Baby (1968), the walls of the apartment close in as the story progresses. Rosemary is surrounded by large, dark furniture—wardrobes, chairs, beds—that seem to dwarf her presence. These pieces aren’t dangerous in themselves, but they shape the room’s energy. They limit escape routes, obstruct lines of sight, and enforce a sense of surveillance. The furniture isn’t blocking her body—it’s squeezing her mind.

The Others (2001) uses furniture under covers as a key visual device. The house is full of draped shapes—sofas, mirrors, dressers—all under ghostly white cloth. The furniture here speaks of absence. No one lives here anymore, but everything remains. It also hints at presence. What’s under the cloth? What’s being hidden? As Nicole Kidman’s character navigates the space, each covered chair becomes a potential body, a potential threat.

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) weaponizes symmetry. The Overlook Hotel is grand, but its beauty is cold and calculated. Long hallways framed by identical armchairs and patterned carpets create a sense of stasis. The furniture doesn’t move—but neither can the characters. Jack’s descent into madness is foreshadowed by the hotel’s sterile arrangement. Every chair is exactly where it’s supposed to be—and that’s terrifying.

Even everyday films like Paranormal Activity rely on room layout to trap characters. The open-plan kitchen and living room, populated with sparse furniture, makes it impossible to hide. The camera captures too much space, and the emptiness itself becomes threatening.

Spatial horror often works best when the viewer feels like they can’t orient themselves. Furniture plays into this disorientation. A table that was in the center of the room is now against the wall. A chair that always faced the TV now faces the hallway. These are small changes—but they scream that something’s off.

Directors use furniture not just as props but as spatial cues. How much space is between the couch and the door? Can a character hide behind the armchair? When a lamp blocks our view of someone walking past, our tension spikes. Horror is in the margins, and furniture defines those margins.

Antique Furniture and Generational Terror

Sometimes, the scariest thing in a horror film is not the ghost—but the cabinet it haunts. Antique furniture in horror is rarely neutral. It arrives with history. Often, it’s inherited. Passed down like an heirloom or a curse.

The Haunting of Hill House (Netflix, 2018) explores this beautifully. The red room, with its ever-changing furniture, reflects each character’s psychological state. For one, it’s a reading nook. For another, it’s a game room. The furniture inside it is never fixed—yet it feels deeply familiar. This fluidity makes the furniture almost alive, tied to family trauma and memory.

In Crimson Peak (2015), Guillermo del Toro designs every piece of Gothic furniture to mirror the decaying aristocracy it belongs to. Elaborate headboards, twisted bed frames, claw-footed sofas—they all scream of a time that should have died but didn’t. The furniture is beautiful, but rotting. It doesn’t just decorate the haunted house—it is the haunted house.

These films link furniture to lineage. A mother’s vanity, a grandfather’s desk—these objects carry more than dust. They carry grief, expectation, secrets. Horror thrives when objects that should bring comfort—familiar chairs, old wardrobes—become evidence of decay and entrapment.

In real life, second-hand furniture can evoke stories of its previous owners. Horror films capitalize on that idea and turn it dark. What if that armoire didn’t just belong to someone before you—but still belongs to them?

Even in productions with modest sets, a single antique piece can shift the tone. A weathered rocking horse in a corner. A grandfather clock with no chime. The atmosphere becomes thick with implication.

Minimalist Furniture and the Horror of Emptiness

Not all horror stems from clutter. In fact, modern horror often terrifies through absence. The stark white walls. The single, too-clean armchair. The unadorned table set for one.

It Follows (2014) plays with this aesthetic. The furniture feels temporary, like it was borrowed for a photo shoot. It exists, but barely. There’s no personality, no permanence. This vacuum amplifies the sense of dread—if no one truly lives here, who will help you when something arrives?

In Get Out (2017), the clean mid-century design of the Armitage household is calm, curated, and deeply menacing. The sterile living room, with its beige couch and tasteful décor, masks control and manipulation. Nothing is out of place—until you realize how controlled everything really is.

This type of horror doesn’t use ornate beds or creaky floors. It uses absence. The room looks fine, but why is there only one chair facing the door? Why is there no clutter, no warmth? The lack of restaurant furniture in an otherwise finished dining space might say more about who—or what—isn’t coming to dinner. Minimalism, in horror, becomes its own kind of scream.

The Silent Witness in the Room

Throughout horror film history, furniture has been more than scenery. It’s been accomplice, narrator, and threat. It’s held memories, and sometimes, it’s held things you’d rather not name.

A couch can comfort—or trap. A crib can nurture—or mourn. Even a simple dining table can take on malevolence when the wrong person sits at it, or when no one sits at all.

And it’s not always about movement. Sometimes, the most frightening thing is the chair that doesn’t rock, the bed that’s too perfectly made, the mirror that’s always clean. Stillness, after all, is its own kind of voice.

So the next time you settle into a horror film, don’t just watch the shadows flicker. Watch the room. Watch the furniture. Listen to what it’s saying—because chances are, it saw what happened before the movie even started. And maybe it’s waiting to tell you.