Walk into the back room of a high-end museum or a professional framing studio, and you will notice something missing. If you flip over a painting worth $50,000, you likely won’t see what 99% of homeowners expect to see.

There is no wire.

To the average person, the “picture wire” is the universal standard. You stretch a steel cable between two screw eyes, you hook it on a nail, and you straighten it until it looks level. It is intuitive. It is forgiving.

But to a conservator or a structural engineer, the picture wire is a geometry problem that, if calculated incorrectly, acts as a torture device for the frame.

The reason professional galleries often abandon the wire isn’t just about stability; it’s about preserving the art itself. Understanding the physics of “Vector Forces” reveals why a tight wire can snap a wooden frame in half, and why the most secure hang might be no wire at all.

The Triangle of Doom

When you hang a picture with a wire, you are creating a triangle. The two corners of the frame are the base points, and the nail on the wall is the apex.

In physics, this arrangement splits the weight of the picture into two distinct forces:

- Vertical Force (Tension): The weight pulling straight down.

- Horizontal Force (Compression): The force pulling the two sides of the frame inward.

This horizontal force is the silent killer.

Imagine a large, heavy mirror with a wire stretched across the back. If the wire is loose and hangs in a deep “V” shape, the tension is mostly vertical. The frame is happy.

But many homeowners hate the “lean” that comes with a loose wire. They want the picture flush against the wall. So, they tighten the wire. They pull it until it is almost a straight line across the back.

This is where the math turns against you. As the angle of the wire at the hook gets flatter (approaching 180 degrees), the horizontal compression force skyrockets.

At a 60-degree angle (a deep V), the stress is manageable. At a 10-degree angle (a tight, flat wire), the inward crushing force can be several times the actual weight of the painting. A 20-pound mirror with a tight wire might be exerting 100 pounds of crushing pressure on its own vertical rails.

Over time, this constant squeezing causes the wood to bow inward. The miters (corner joints) pop open. If the frame is holding a canvas, the canvas wrinkles. If it is holding glass, the glass can shatter under the stress of the distorted frame.

The “D-Ring” Standard

This is why, for heavier or larger pieces, professionals skip the wire entirely.

Instead, they use the “Two-Point” hanging system. They attach heavy-duty D-rings (steel loops shaped like the letter D) to the vertical rails of the frame. Instead of stringing a wire between them, they simply hang the D-rings directly onto two separate hooks on the wall.

This method eliminates the vector problem instantly.

- Zero Compression: Because there is no wire pulling the sides together, there is zero inward force. The frame only experiences vertical gravity, which it is designed to handle.

- Zero Swing: A picture on a single wire acts like a pendulum. A door slams, and the picture goes crooked. A picture on two hooks is structurally locked in place. It will never need straightening.

The “French Cleat” Alternative

For extremely heavy items or situations where two hooks seem too difficult to measure, the industry standard shifts to the French Cleat (or Z-Bar).

This is a two-part system. One metal rail is screwed into the wall (ideally into studs); the mating rail is screwed into the back of the frame. They interlock like a puzzle piece.

The physics here are superior because of “Load Distribution.” A wire puts all the weight on two tiny screw holes. A cleat spreads the weight across the entire width of the frame. It essentially turns the top rail of the frame into a load-bearing shelf.

When You Must Use Wire

Of course, the wire isn’t going away. It is convenient, and for light, small pictures, the compression forces are negligible. But if you must use wire, there are rules to follow to prevent damage.

- Respect the Slack: Never tighten the wire to reduce the “lean.” If the picture is leaning too far forward, the solution isn’t a tighter wire; the solution is moving the attachment points higher up the frame (roughly 1/4 to 1/3 down from the top). You need the slack to keep the vector angle safe.

- The 60-Degree Rule: Aim for the wire to form an internal angle of about 60 degrees at the hook. This balances the vertical and horizontal forces.

- Use the Right Knot: A slipping knot is a falling picture. The standard “twist it around itself” method is often insufficient for heavy coated wire. Professionals use a “locking wrap” technique—threading the wire through the eye, wrapping it back around the eye once, and then coiling it tightly around the standing part of the wire.

The Material Fatigue Factor

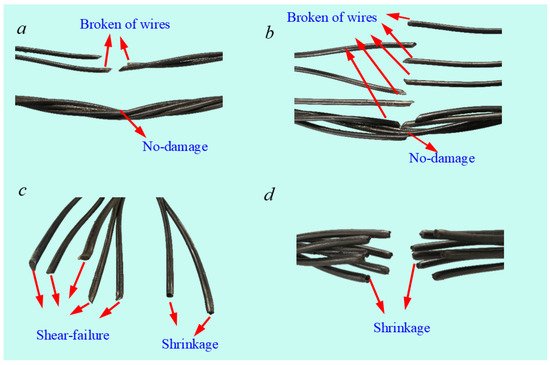

Finally, there is the wire itself. Most “picture wire” is braided steel strands. Over time, metal fatigues.

Every time a door slams or a truck drives by, the wall vibrates. The wire rubs against the hook. This microscopic sawing action creates a wear point. If the wire is kinked or if it is an old-school single-strand copper wire, it can snap without warning.

Coated wire (steel wrapped in vinyl) is the modern standard because the vinyl acts as a lubricant and a buffer, preventing the steel from sawing against the hook.

Conclusion

Hanging art is often treated as the final, rushed step of decorating. We grab a hammer, eyeball the height, and hope for the best.

But when you hang a piece of art, you are building a small structural system. You are fighting gravity. If you ignore the geometry of that system, gravity eventually wins.

Whether you choose to embrace the two-point hang or stick with the traditional wire, understanding the forces at play ensures your collection stays on the wall, not on the floor. It turns out that the most important component of art hanging hardware isn’t the metal hook you buy at the store, but the invisible angles you create on the back of the frame.