Have you ever watched someone deliver a threat through gritted teeth, their words hissing and clipped, barely escaping the fortress of their jaw? There’s actually a word for that: dentiloquent. This nearly extinct adjective describes the act of speaking with your teeth closed or clenched—a phenomenon you’ve witnessed countless times but probably never had the vocabulary to name.

Dentiloquent (pronounced den-TIL-oh-kwent) comes from the Latin denti- (teeth) and loqui (to speak). While you won’t find it in everyday conversation or even most modern dictionaries, this linguistic relic offers a precise way to describe a specific manner of speech that conveys tension, anger, restraint, or even secretiveness.

But dentiloquence is more than just a curiosity for word lovers. Understanding this forgotten term opens a window into Victorian-era vocabulary, the physiology of restricted speech, and how physical expression shapes psychological states. This exploration will take you from the dusty corners of 19th-century lexicons to contemporary literature, revealing why some words deserve resurrection—and how expanding your vocabulary with these rarities can sharpen both your writing and observation skills.

The Victorian obsession with linguistic precision

The 19th century was a golden age for obscure vocabulary. Victorians had an almost pathological need to categorize and label every conceivable human experience, emotion, and behavior. This era gave us words like petrichor (the smell of rain on dry earth), apricity (the warmth of the sun in winter), and dentiloquent.

These weren’t merely academic exercises. Victorian society valued eloquence and specificity in language as markers of education and social standing. A well-read person could distinguish between being lachrymose (tearful) and lugubriose (mournful), or describe someone as ructious (quarrelsome) rather than simply “difficult.”

Dentiloquent emerged during this period of linguistic expansion, likely appearing in medical texts before making its way into more general usage. Doctors and anatomists of the era were fascinated by the mechanics of speech production, cataloging every variation in articulation. The term would have been particularly useful for describing patients with conditions affecting jaw mobility or for characterizing speech patterns associated with certain emotional states.

Many of these Victorian-era words have faded from use, victims of linguistic evolution and the modern preference for simpler, more accessible language. Yet their specificity offers something our streamlined vocabulary often lacks: the ability to capture nuanced distinctions with a single, carefully chosen word.

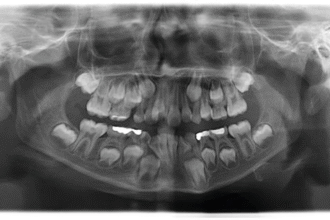

The mechanics of speaking through clenched teeth

To understand dentiloquence fully, we need to examine what actually happens when someone speaks with their teeth closed or nearly closed. The process involves significant modifications to normal speech production.

Speech typically requires free movement of the jaw, tongue, lips, and soft palate. When the teeth are clenched, the jaw becomes locked in a fixed position, severely limiting the oral cavity’s ability to reshape itself for different sounds. This creates several challenges:

Restricted resonance: The oral cavity acts as a resonating chamber that gives each vowel its distinctive quality. Clenching the teeth reduces this space, creating a compressed, nasal quality to the voice.

Modified consonant production: Many consonants rely on precise positioning of the tongue against the teeth or palate. With clenched teeth, speakers must find alternative articulation strategies, often resulting in distorted sounds.

Increased nasalization: When the mouth is restricted, more air flows through the nasal passages, giving speech a characteristic nasal tone.

Muscle tension: Maintaining a clenched jaw requires sustained muscle contraction throughout the speech mechanism, creating vocal strain and a harsh quality.

Dentiloquent speech typically results in a sound that’s simultaneously hissing, muffled, and strained—think of a villain delivering a warning or someone trying to argue quietly in a public place. The physical restriction mirrors emotional restriction, which is why this speech pattern so effectively communicates suppressed anger, forced restraint, or simmering hostility.

Interestingly, some forms of ventriloquism utilize controlled dentiloquent techniques. Ventriloquists learn to speak with minimal jaw movement, though they typically maintain slightly parted teeth rather than fully clenched ones. This demonstrates that with training, remarkably clear speech is possible even with significant oral restriction.

Dentiloquence as a literary device

Writers have long recognized the expressive power of dentiloquent speech, even if they didn’t always have the term to describe it. When an author notes that a character spoke “through gritted teeth” or “with a clenched jaw,” they’re invoking dentiloquence to convey emotional subtext.

In Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Mr. Rochester frequently speaks with restrained intensity that suggests clenched-jaw delivery, particularly during emotionally charged exchanges. His dialogue often carries an undertone of barely controlled passion or frustration that readers can almost hear in the compressed, forceful quality of his words.

Similarly, in crime and thriller fiction, dentiloquent speech serves as shorthand for threats delivered with cold control. A gangster who says “You’ve got twenty-four hours” through clenched teeth conveys far more menace than one who speaks the same words casually. The physical restriction suggests barely restrained violence—a pressure cooker ready to explode.

Modern screenwriters understand this instinctively. Consider Clint Eastwood’s iconic performances, where much of his character’s intensity comes from his famously dentiloquent delivery. His clenched-jaw speaking style became synonymous with controlled masculine anger and became so distinctive it inspired countless imitations.

The technique also appears in more subtle contexts. Characters experiencing shame, embarrassment, or social discomfort might speak dentiloquently as they attempt to maintain composure while internally struggling. A teenager grudgingly apologizing to a parent, a professional maintaining politeness with a difficult client, or someone holding back tears during a difficult conversation might all exhibit dentiloquent speech patterns.

By naming this pattern, writers gain a tool for more precise character description. Rather than repeatedly describing how a character speaks through clenched teeth, you might describe them once as habitually dentiloquent, establishing this as a character trait that readers will continue to “hear” in subsequent dialogue.

The psychology of restricted speech

The relationship between physical expression and emotional state runs both ways. We clench our jaws when angry or tense, but research also suggests that forced jaw clenching can actually intensify feelings of stress and aggression. This bidirectional relationship makes dentiloquent speech particularly interesting from a psychological perspective.

When someone adopts a dentiloquent speaking pattern, they’re engaging in a form of physical self-restraint. The clenched jaw serves as a literal barrier, preventing words from flowing freely. This can represent:

Suppressed emotion: The speaker wants to maintain control despite strong feelings, creating a pressure between expression and restraint.

Social propriety: In situations where open anger or disagreement is inappropriate, dentiloquent speech allows limited expression while maintaining surface civility.

Power dynamics: Speaking through clenched teeth can be a way of communicating displeasure while maintaining plausible deniability—the words might be polite, but the delivery signals hostility.

Self-protection: Sometimes dentiloquent speech protects the speaker from their own emotions, as if the physical barrier prevents feelings from fully emerging.

Chronic dentiloquent speech patterns can indicate unresolved anger, difficulty with emotional expression, or excessive self-control. Some people develop habitual jaw clenching (a condition called bruxism) that extends into their speech patterns, often linked to chronic stress or anxiety.

Conversely, deliberately adopting a more open, relaxed jaw position when speaking can help reduce feelings of tension and hostility. This is why many anger management and stress reduction techniques include exercises for jaw relaxation. By releasing the physical restriction, emotional restriction often follows.

Understanding dentiloquence gives us insight into how physical expression shapes psychological experience. The next time you notice yourself or someone else speaking through clenched teeth, you’re witnessing the embodiment of emotional constraint—the body literally holding back what the mind won’t release.

Expanding your vocabulary with forgotten words

Dentiloquent represents just one example of the thousands of precise, evocative words that have fallen out of common usage. Reviving these linguistic fossils offers several benefits for writers, communicators, and anyone who loves language.

Precision over approximation: Modern English often settles for close-enough descriptions. We use “sad” for experiences ranging from mild disappointment to devastating grief. Victorian vocabulary offered gradations: tristful, dolorous, lachrymose, lugubrious, and melancholic each capture different shades of sadness. Similarly, dentiloquent offers precision that “speaking through gritted teeth” can only approximate.

Fresh perspectives: Obscure words often highlight distinctions we’ve stopped noticing. Learning that ultracrepidarian means “someone who gives opinions on subjects they know nothing about” suddenly makes you more aware of this behavior. Dentiloquent draws attention to a specific speech pattern you might have witnessed but never isolated as a distinct phenomenon.

Creative inspiration: Writers can use rare words strategically to create specific effects. A character described as dentiloquent gains immediate dimensionality. The word itself sounds harsh and compressed, mirroring the speech pattern it describes—an example of phonetic appropriateness that adds layers of meaning.

Intellectual pleasure: There’s genuine joy in discovering the perfect word for something you’ve experienced but couldn’t name. It’s like finding out that sonder describes the realization that each passerby has a life as complex as your own, or that kenopsia captures the eerie atmosphere of abandoned places. These words validate experiences and observations, giving them legitimacy through linguistic recognition.

To build your vocabulary with forgotten words, explore Victorian-era literature, browse historical dictionaries, and investigate etymology resources. The Oxford English Dictionary’s historical citations show how words were used in context. Websites like Phrontistery and World Wide Words catalog obscure and obsolete terms. Social media accounts dedicated to rare words offer daily discoveries.

When you encounter words like dentiloquent, don’t just collect them—use them. Try incorporating one forgotten word per week into your writing or conversation. This practice keeps these linguistic treasures alive while sharpening your own expressive capabilities.

The enduring appeal of words that capture precise moments

Dentiloquent will likely never become common parlance. Most people will continue saying “through gritted teeth” rather than adopting this Victorian specimen. Yet the word’s existence matters because it represents something fundamental about human communication: our need to name and understand the nuances of experience.

Every forgotten word is a small tragedy—a concept someone once thought important enough to label, now slipping toward extinction. But every revival is a victory, proof that language can grow by looking backward as well as forward.

Whether you’re a writer seeking fresher ways to describe your characters, a language enthusiast delighted by precision, or simply someone who appreciates the strange corners of English vocabulary, dentiloquent offers something valuable. It gives you new eyes (or ears) for a common phenomenon, transforming an overlooked detail into a recognizable pattern.

The next time you notice someone delivering words through a clenched jaw—in anger, restraint, or stubborn determination—you’ll have the perfect word. And perhaps, in using it, you’ll give this forgotten term another chance at life, proving that even the most obscure corners of our vocabulary deserve occasional resurrection.

After all, language is richest when it offers us not just adequate words, but perfect ones.